The questions of arbitration clauses and subsequent arbitration proceedings have already been brought before the European Court of Human (hereinafter „the Court“). Most notably, the Court held that arbitration is not incompatible with the European Convention on Human Rights (hereinafter „the Convention“), established in Transado - Transportes Fluviais Do Sado, S.A. v. Portugal (dec.), 2003. In Eiffage S.A. and Others v. Switzerland. 2009 and Tabbane v. Switzerland, 2016, para. 27, the Court held that by accepting an arbitration clause, the parties voluntarily waive certain rights enshrined in the Convention.

Mutu and Pechstein v. Switzerland, a judgement rendered in February 2019, further elaborated this concept. Two applicants were sportsmen and had complaints regarding their sporting activities. However, one of them (the second applicant) was forced by his contract to address his complaints solely by means of arbitration making the subsequent arbitration compulsory. The first applicant did not have such a strict prerequisite making the arbitration voluntary. The Court stated the following:

95. “In addition, a distinction must be drawn between voluntary arbitration and compulsory arbitration. If arbitration is compulsory, in the sense of being required by law, the parties have no option but to refer their dispute to an arbitral tribunal, which must afford the safeguards secured by Article 6 § 1 of the Convention.

96. However, in the case of voluntary arbitration to which consent has been freely given, no real issue arises under Article 6. The parties to a dispute are free to take certain disagreements arising under a contract to a body other than an ordinary court of law. By signing an arbitration clause, the parties voluntarily waive certain rights secured by the Convention. Such a waiver is not incompatible with the Convention provided it is established in a free, lawful and unequivocal manner.”

1) Procedural rights from Article 6 of the Convention are contextual Firstly, what is Article 6 of theConvention? It is a procedural article protecting the right to a fair trial (fair and public hearing within a reasonable time, independent and impartial tribunal presumption of innocence, certain minimum rights in criminal proceedings etc.) That being said, let us come back to our premise. Every human right depends on the context. The freedom of speech will be limited if it is used for hate speech. The right to privacy will be limited for people with a public status. The Court itself says when interpreting Article 6 of the Convention that the article is not absolute but rather subject to limitations. (Stanev v. Bulgaria, para. 135) However, being dependent on the context and being contextual are two widely different things. Being dependent on the context means that the right is not unlimited. Being contextual means that the right is limited. Being not unlimited means that in certain cases their applicability will not be upheld. Being limited means that in certain cases their applicability is not meant to be upheld. In this case, procedural rights were never meant to be safeguarded in compulsory arbitration. This limitation does not exist in relation to the outside world (event that is the subject of the claim before the tribunal) but rather in relation to a legal procedure, a procedure that was accepted by the Court as a viable alternative to court proceedings. This is the main manifestation of such a limit. When a right is upheld procedurally, but not unlimited, the applicable instances are distinguished by a case-by-case approach. However, if the procedure is limited, substantial issues become irrelevant altogether because the parties do not have a way of addressing them in the first place. In conclusion, it is true and should be noted that reserving the applicability of human rights when it comes to arbitration does create the notion that fair trial rights are not inherent in individuals but rather in different forms of procedures, they find themselves in. It also puts a nail in the coffin of whether fair trial rights are actually human after all. This may seem like a harsh judgement but it is one that has to be considered. Theoretical dimension of human rights is important as it creates the basis for practical reasoning and a threshold that must never be crossed.

2) What Article 6 rights are specifically waived? The judgement only states that certain rights, and more specifically, certain Article 6 rights are herewith waived but fails to mention which ones. Determining in greater detail which rights are waived and which are not will therefore probably be determined on a case-by-case basis. However, since court practice is not abundant in this field, the precise practical nature of which rights ought to be waived will remain unspecified for some time to come.

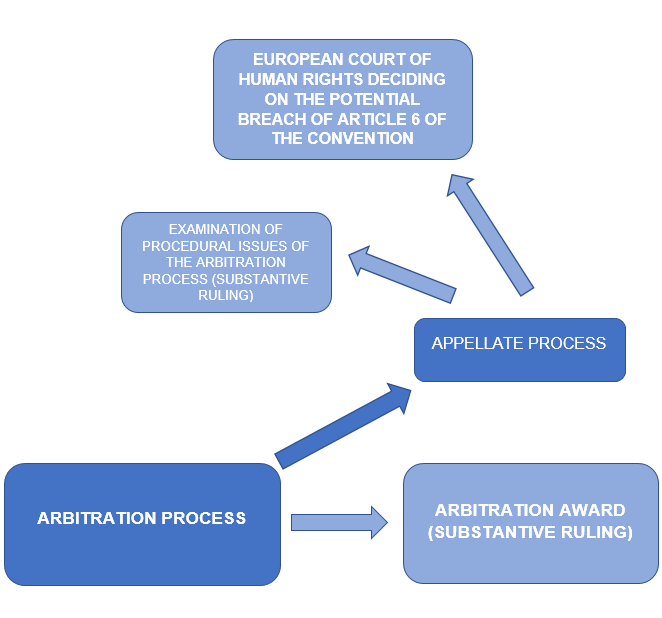

3) Should parties be safeguarded by the EuropeanConvention of Human Rights in arbitral proceedings? It is important to note that procedural rights of the parties are still in most cases safeguarded, just not in the form of human rights. Most states provide for formal appeals in arbitral proceedings. However, the reason why human rights exist in the form of a legal institute is to provide for necessary protection in case states fail to uphold human rights to the necessary standard. The parties in this case will be able to claim potential human rights violations in front of the Court that emanate from the appellate process but not from the arbitral process as well. It is also important to notice that the ruling of the appellate court on procedural issues in the arbitral process is a substantive ruling. Therefore, the subsequent human rights challenge of the appellate procedure based in the Article 6 of the Convention only pertains to the appellate process and has no connection to the arbitral procedure because arbitral procedure is in a substantive form in that case and not covered by Article 6 of the Convention.

The foremost question therefore remains, both theoretical and practical; should the parties still be protected even though they themselves chose to bring their case to arbitration and crafted the procedure to their liking? It is undoubtable that arbitration offers a great deal of autonomy and independence when it comes to shaping the procedure. That autonomy is, however, not unlimited. Both parties are involved in the process of reaching a consensus when it comes to constructing an arbitral clause and creating the framework of the subsequent proceeding. Arbitrators, once selected, are independent and beyond the parties' control. The notion of independence and autonomy in drafting the arbitral framework has no bearing on the amount of immediate control the parties have in the proceeding itself. In mediation for example, the parties always remain in full control, and the epitome of that control is clearly visible from the fact that they are not bound by any potential resolution proposed by the mediator. Also, both parties are able to exit the mediation proceeding whenever they choose to do so. Parties to an arbitral proceeding exert considerable control in the beginning until they become bound by the arbitral agreement. Their control in relation to the tribunal and the award being rendered is limited from that point on and much more similar to a regular court proceeding.